ILEC Observations

Whole Life vs Universal Life

Introduction

Monitoring industry experience (mortality, morbidity, lapses) is a key

objective for Munich Re’s North American biometric research team.

We hope to stimulate discussions with our business partners and

across the insurance industry by sharing our key findings. We believe

these discussions will lead to a better understanding of the emerging

experience and its importance in assessing the underlying risk.

This paper is the third in a series looking at the data provided by

the most recent Individual Life Insurance Mortality Report from

the Individual Life Experience Committee (ILEC) of the Society of

Actuaries. However, this paper is the first to include the latest 2014-15

calendar year ILEC data, which supplemented the prior 2009-13 study.

Earlier papers explored preferred wear-o, post-level term mortality

(click here) and variation in the underlying experience by the number

of preferred classes and type of product (click here). This paper will

further expand upon experience by product type, with a specific

focus on universal life and how it compares to its term and whole life

predecessors. Before diving into the experience, it is important to

be familiar with the history of these products and to understand the

market conditions during the time period when they were sold and

why they appealed to so many policyholders.

MUNICH RE LIFE US

ILEC Observations – Whole Life vs Universal Life 2/4

© 2019 Munich American Reassurance Company, Atlanta, Georgia

The Rise of Universal Life

Life insurance companies experienced a diicult period

during the late 1970s and early 1980s when the United

States was experiencing a period of historically high

interest rates.

1

At the time, yields on new investments

were significantly higher than the portfolio rates credited

on whole life cash value products. Policyholders began

surrendering their whole life products in order to invest

the cash value in the high yielding bond market.

2

This, in

turn, put downward pressure on term premium rates as

these same policyholders replaced their whole life coverage

with term insurance, materially increasing the number

of new applications in the term insurance market. In

order to maintain market share, companies repriced their

term products on a continual basis, with rates spiraling

downward. Term lapse rates began to rise significantly as

healthy individuals were re-underwritten each year in order

to take advantage of the new, lower premium rates.

3

Insurance companies became concerned that there would

be a significant shift in invested assets from cash value

insurance products to the financial markets, potentially

leading to liquidity and solvency pressures.

4

This is the genesis of the universal life (UL) product. At the

time, it was seen as a potential solution to these market

conditions. As a hybrid product, it combined the benefits

of illustrating high investment returns with charging

competitive term insurance rates in the early years.

4

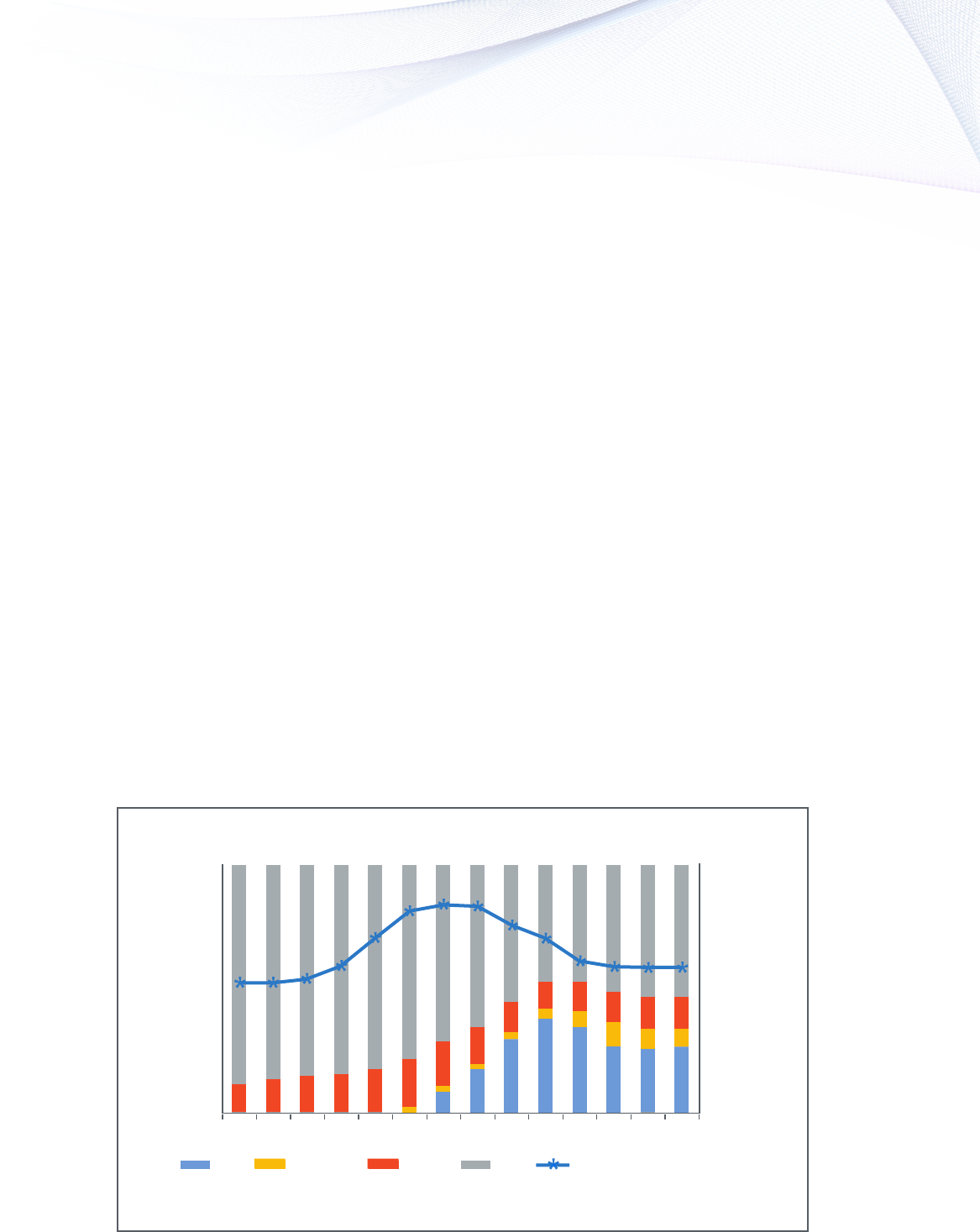

Compared to whole life, the universal life design was touted

widely as being “transparent,” where the policyowner could

see all the factors that determined their UL account value:

premiums received, interest credited, deductions from

premium loads, administrative fees and cost of insurance

(COI) charges.

5

Furthermore, UL insurers were able to

illustrate using rates of interest significantly higher than the

dividend interest rates embedded in whole life policies in the

early 1980s. As such, market share quickly began to migrate

from whole life to universal life, as shown in Graph 1.

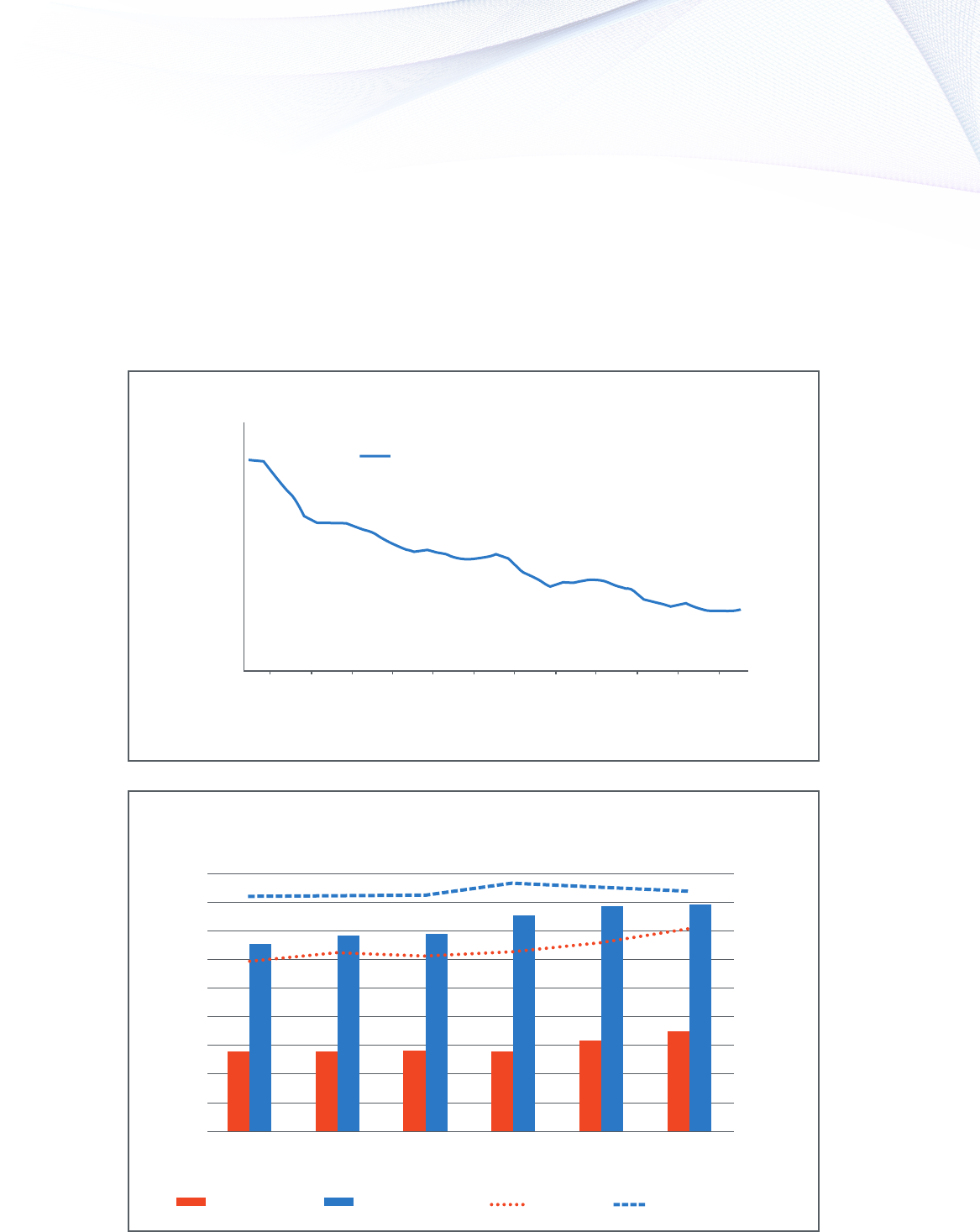

Several years later, as interest rates began to decline

in the mid 1980s, so did the non-guaranteed returns

of the universal life policies. Eventually, earned rates

reached the guaranteed minimum rates specified in these

policies, which were approximately 4-5%

5

(see Graph 2).

Account values started to deviate significantly from policy

illustrations. In addition, the investment returns on the

account values were not enough to cover the increases in

cost of insurance charges, and policyholders were required

to pay substantially more premiums in order to keep the

policies in force.

6

This resulted in reputational challenges

for the life insurance industry including multiple “class

action lawsuits and individual litigation claiming the

insurance companies had used unrealistic projections of

future interest rates in their illustrations.”

7

This led to lower

persistency and subsequent deterioration in mortality

experience for life insurance companies.

Persistency and Mortality

In our proprietary studies, we have observed that lapse

experience for these first-generation universal life products,

sold in the 1980s and 1990s, has been higher than lapse

experience on whole life products. While whole life lapses

Percent of New Business

New Money Rate

100% –

90% –

80% –

70% –

60% –

50% –

40% –

30% –

20% –

10% –

0% –

– 16.0%

– 14.0%

– 12.0%

– 10.0%

– 8.0%

– 6.0%

– 4.0%

– 2.0%

– 0.0%

Graph 1: Sales by Product vs New Money Rates

UL Variable Term WL AAA Corporate Bond Yield

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

Sources: U.S. Individual Life Insurance Sale Trends, 1975-2013, LIMRA Insurance Research, September 2014

Moody‘s AAA Corporate Bond Yield, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (3 year moving average)

ILEC Observations – Whole Life vs Universal Life 3/4

© 2019 Munich American Reassurance Company, Atlanta, Georgia

trend down towards an ultimate lapse rate, the higher

universal life lapse experience starts as early as duration 10

for some portfolios and continues to increase as time goes

on. This timing is not surprising, given that a UL surrender

charge ”generally declines to zero over 10 to 15 years and

allows the insurer to recover first year commissions and

other acquisition expenses out of subsequent margins.”

5

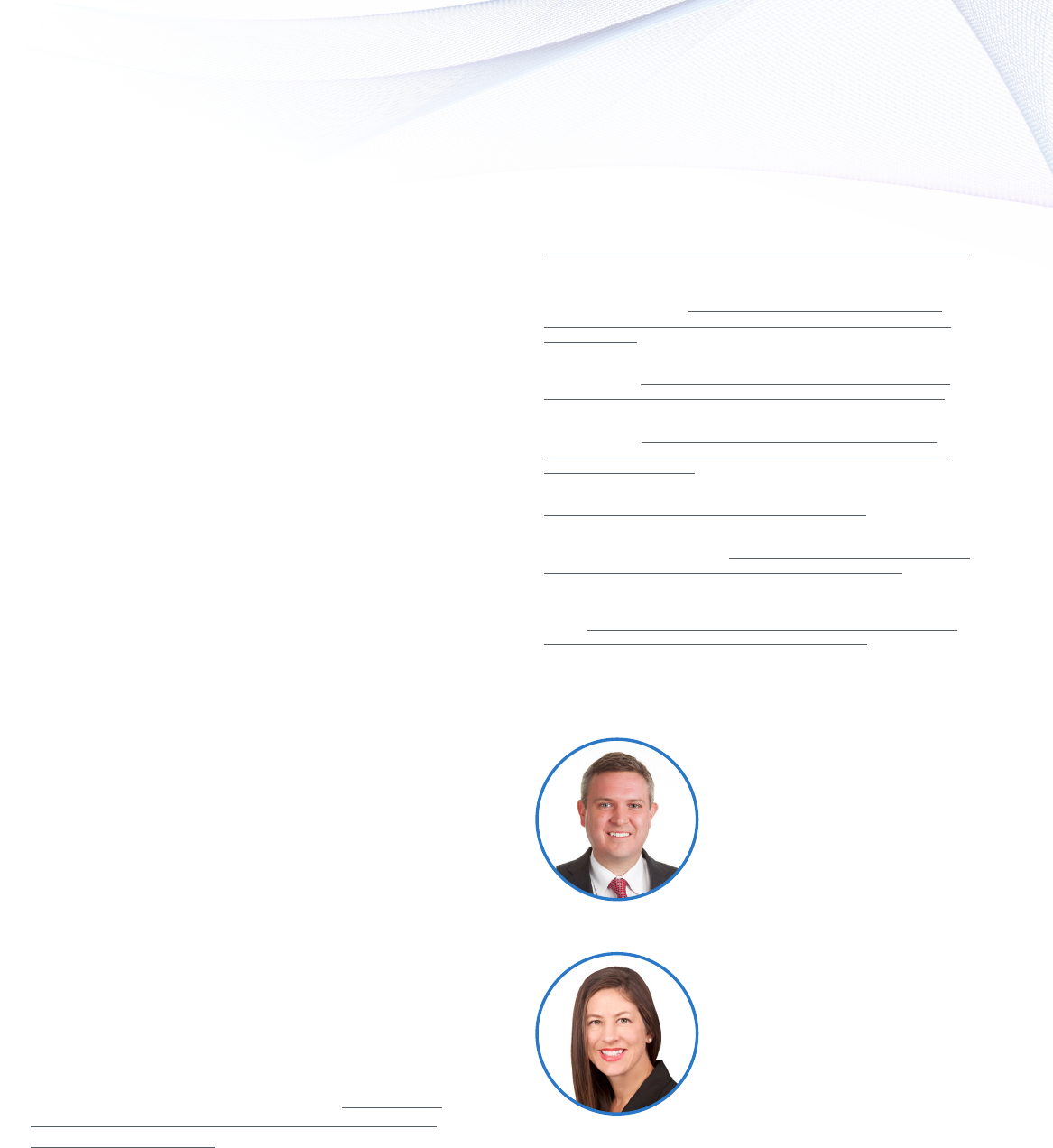

Concurrent with this lapse deviation, we also observed

a corresponding increase in UL mortality that can be

approximated using Duke’s MacDonald methods where the

anti-selective lapse factor is set equal to the excess of the

universal life lapse rates over the whole life lapse rates with

a near 100% eectiveness assumption.

This same phenomenon continues into later durations and

can be observed in the 2009-2015 ILEC data. Graph 3 shows

the mortality A/E for universal life and whole life products

for key insurance ages from the 1984-1989 sales cohort.

8

Source: Moody‘s AAA Corporate Bond Yield, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (3 year moving average)

16.0% –

14.0% –

12.0% –

10.0% –

8.0% –

6.0% –

4.0% –

2.0% –

0.0% –

Graph 2

Graph 3

Male 100K-2,499K IA 30-59, IY 1984-89

1982

1985

1988

1991

1994

1997

2000

2003

2006

2009

2012

2015

2018

Year

Yield

Lapse Rate by Count

AE(VBT15) by Count

Duration

9.0%

8.0%

7.0%

6.0%

5.0%

4.0%

3.0%

2.0%

1.0%

0.0%

120.0%

100.0%

80.0%

60.0%

40.0%

20.0%

0.0%

26 27 28 29 30 31

WL Lapse Rate UL&VL Lapse Rate WL A/E(#) UL&VL A/E(#)

AAA Corporate Bond Yield

ILEC Observations – Whole Life vs Universal Life 4/4

© 2019 Munich American Reassurance Company, Atlanta, Georgia

Industry Response and Today

Since the time of the first-generation universal life

products, many innovative product designs have entered

the universal life market, such as the no-lapse guarantee

(NLG) feature. In addition, illustration regulations were

introduced to inform and protect life insurance consumers,

thereby making the current sales environment much

dierent than it had been in the past. We anticipate that

these changes will flow through to policyholder behavior.

For example, we do not see, and would not expect to see,

the same lapse and mortality deterioration to emerge in

NLG universal life product experience as we saw in the

earlier UL products.

However, questions remain. First-generation universal

life products were sold with returns on account values on

the order of 10%

7

with contractual guaranteed minimum

earned rates on the order of 5%. Currently, many UL

products have a guaranteed minimum earned rate of

approximately 1%. Would illustrations of 6% tempt fate

to repeat the poor experience of the first generation ULs

if actual investment returns significantly underperform

such illustrations?

Conclusion

We have outlined some of the experience variation that

could be useful in setting mortality assumptions for WL

and UL products. The ILEC data is a valuable source

of recently emerged industry experience. However, a

significant heterogeneity of the data should be taken into

account by any user in their own work. Actuaries should

also try to understand the drivers in the historic data so

that they can use sound judgement when setting best

estimate assumptions for future business.

It is also important to keep in mind that policyholder

behavior is very much influenced by external forces.

So, while we can gather valuable insight from historical

experience, it should be only one of many factors taken into

consideration when setting assumptions.

Again, we believe that sharing some of our findings will

stimulate further discussion and will lead to better under-

standing of the key drivers behind emerged experience.

Note: The ILEC data files can be found at https://www.

soa.org/resources/research-reports/2019/2009-2015-

individual-life-mortality/

References

1. The US Prime rate hit a record high of 21.50% on December 19th 1980.

http://www.fedprimerate.com/wall_street_journal_prime_rate_history.htm

2. Transactions of Society of Actuaries, 1980, Vol. 32, Pricing a Select

and Ultimate Annual Renewable Term Product, Jeery Dukes &

Andrew M. MacDonald. https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/

library/research/transactions-of-society-of-actuaries/1980/january/

tsa80v3216.pdf

3. Record of Society of Actuaries, 1985, Vol. 11, No. 1, New Developments –

Term Insurance, https://www.soa.org/library/proceedings/record-of-

the-society-of-actuaries/1980-89/1985/january/RSA85V11N119.pdf

4. A Brief History of Universal Life, Douglas C. Doll, The Universal

Life Study Note, https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/library/

monographs/50th-anniversary/product-development-section/1999/

january/m-as99-3-06.pdf

5. Further Observations on Life Insurance, James H. Hunt, 2013,

https://consumerfed.org/pdfs/Evaluate-June-2013.pdf

6. Universal Life Insurance, a 1980s Sensation Has Backfired, Leslie

Scism, The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/universal-

life-insurance-a-1980s-sensation-has-backfired-1537368656

7. The Financial Basis for No Lapse Universal Life Insurance, Academy

of Financial Services, 2010 Annual Meeting, Lise Graham & David R.

Lange, https://academyoinancialservices.wildapricot.org/resources/

Documents/Proceedings/2010/4A-Graham-Lange.pdf

8. Although the ILEC study is a mortality study and not a lapse study, we

have calculated implied lapse rates based on changes in the exposures.

The results are consistent with what we observe in proprietary studies.

Tim Morant

FSA, MAAA

VP & Actuary,

Biometric Research

Munich Re Life US

Lisa Seeman

FSA, MAAA

2nd VP & Actuary,

Biometric Research

Munich Re Life US